Exploring Padova's Fluvial Heritage: Insights from a Transdisciplinary Experience

Nestled in northern Italy near Venice, Padova is a city shaped by the courses of the Brenta and Bacchiglione rivers. This historically significant fluvial city has been molded by its natural and artificial water bodies, making it a unique landscape to explore. From the 13th century onwards, the Venetians constructed extensive artificial canals to interlink the two river catchments, primarily establishing a convenient connection between Padova and Venice. In the 19th and 20th centuries, new bigger canals were dug to protect Padova from flood events. Today, the canals weave through this European cityscape adorned with old buildings and historic chapels.

The River Cities Network (RCN) began its conversation on the complex nature of rivers in the Anthropocene in Padova. This article reflects on that conversation, divided into three parts: Fieldwork, Group Work, and Lessons Learned.

By Yasmin Ahmed Abdelaziz Hafez, Alex Faccin, Sankha Subhra Nath and Satya Maia Patchineelam.

Fieldwork: Embracing Padova’s Waterscapes

Our journey into Padova's fluvial heritage began with a fieldwork expedition to explore the adaptations and solutions evident in the canals and the biodiversity of the river, where the river served as our entry point. Sitting in a boat, we passed from the Tronco Maestro channel to the Bacchiglione River through the small gate at Cavai’s bridge. We experienced a fascinating transition. As we moved from the urban canal, brimming with aquatic vegetation and lined with large trees, to the wide river, which had less vegetation and more urban features emerged in the background.

This transition from canal to river revealed diverse waterscapes with distinct characteristics and sensations. The narrow canal, filled with natural elements, flows into the heart of the city, while the wide river, situated outside the city, becomes a playground for aquatic sports like rowing. It was intriguing to see how the city’s relationship with water has reversed from its medieval/ancient usage, relegating active human engagement to the river's outskirts while the ancient urban canals within the city are thriving with biodiversity in forgotten spaces.

Young man rowing in Bacchiglione river upstream of Padova. Alex Faccin, September 2023.

Group Work: Collaborative Conservation/ Resuscitation/ Rejuvenation Planning

To further familiarize ourselves with Padova, we engaged in a group project to imagine conservation plans for the city's canals and water systems. Divided into teams based on our areas of expertise, each group included members from different disciplines, making the collaboration dynamic and enriching. Our team comprised a social scientist, two architects, and an environmental engineer. We had three days to come up with ideas to re-integrate the river into citizens' lives.

From a series of walks along the canal and subsequent discussions, we identified that the canal was disconnected from the people passing along it due to landscape obstacles and physical barriers/elements. This transdisciplinary project allowed us to combine our knowledge and perspectives. We employed an urban acupuncture method- identifying pressure points in the urban fabric, and mapped our emotional responses while walking along the river. We pinpointed elements that were positive or negative and used this data to propose ideas to make the riverbank more inviting for citizens.

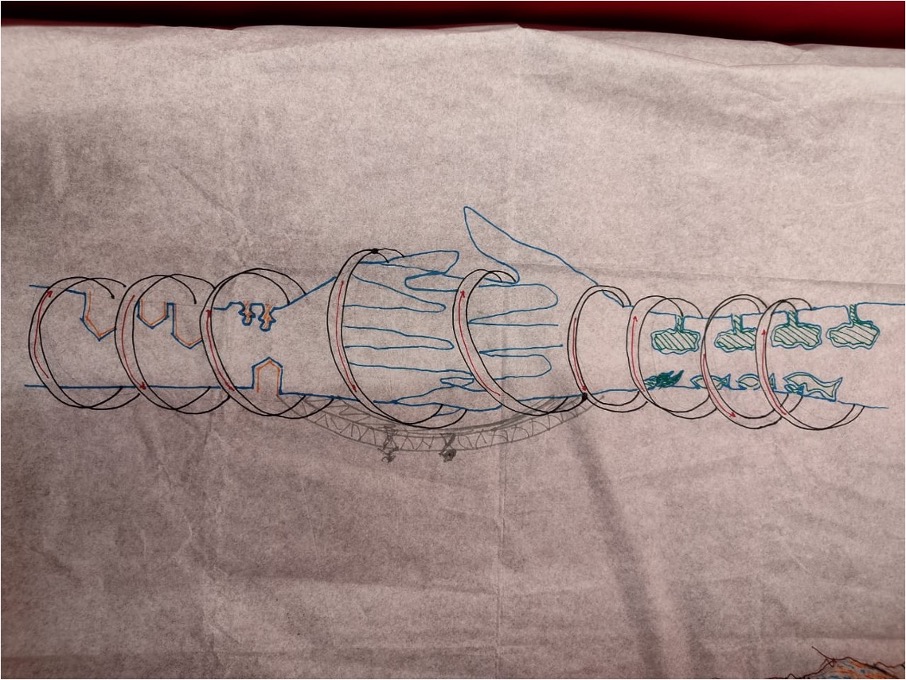

In this respect, Satya Maia Patchineelam's illustration (see below) depicted the socio-ecological dynamics of the canal and its interaction with the surrounding citizens. It highlighted the continuous effort required to connect nature and urban planning successfully. This drawing also underscored the necessity of interdisciplinary work and conversations for effective nature conservation and management.

Illustration by Satya Maia Patchineelam, September 2023.

Lessons Learned: The Values and Challenges of Transdisciplinary Work

Our experience reinforced the values and challenges of transdisciplinary work. Collaborating closely with individuals from diverse backgrounds unlocked a wealth of insights and solutions that would have otherwise been unattainable. It also provided us with opportunities for personal growth and self-discovery. However, we quickly realized that communication could be quite challenging when team members spoke different sectoral languages. In these instances, our ability to listen, practice patience, and maintain mutual respect became critically important.

One major hurdle we faced was navigating the technical language barriers, which forced us to rethink our methods of expression. Creativity became our ally, allowing us to ensure our ideas were understood. Each team member appreciated this exercise, resulting in innovative and interesting outcomes. Working with people from different countries, cultural backgrounds and languages could have been limiting. We found that these barriers didn’t solely determine the quality of our interactions, but reflected also in the quality of our work.

The course expanded our understanding and perspective of Padova and its canals. Attending lectures from various disciplines allowed us to explore a single topic through multiple lenses, broadening our knowledge and appreciation. This experience taught us to view challenges as opportunities for growth and to embrace the diverse perspectives that transdisciplinary work brings.

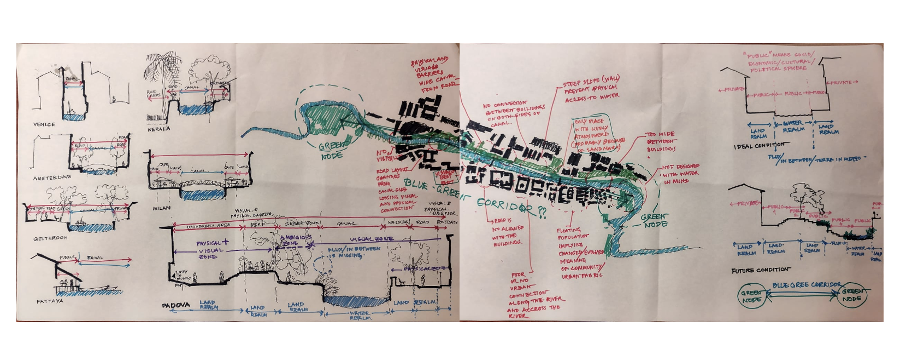

The sketch below by Sankha Subhra Nath tries to incorporate different perspectives and challenges of the study area. It also tries to conceptualize probable solutions to overcome the challenges.

Sketch by Sankha Subhra Nath, September 2023.

Reflections on Padova's Changing Environmental Challenges

Beyond personal experiences, Padova taught us a crucial lesson about environmental challenges. Historically, the city feared floods, but climate change has now brought devastating droughts to Italy. With changing environmental challenges, researchers are exploring new solutions, including involving members of local communities (such as local fishermen) and implementing applications that mimic the functionalities of natural components, i.e., the so-called Nature-based Solutions. The lesson here is that just because humans have managed/controlled water in the past doesn’t mean it will always be manageable and constant in the future. This requires continuous teamwork, innovative thinking, and ongoing reflection.

In conclusion, our time in Padova underscored the importance of transdisciplinary collaboration and the ever-evolving relationship between humans and water. The insights gained from this experience will undoubtedly shape our future endeavors in understanding and managing the intricate dynamics of urban waterscapes.

The Specola old observatory tower. Yasmine Hafez, September 2023.